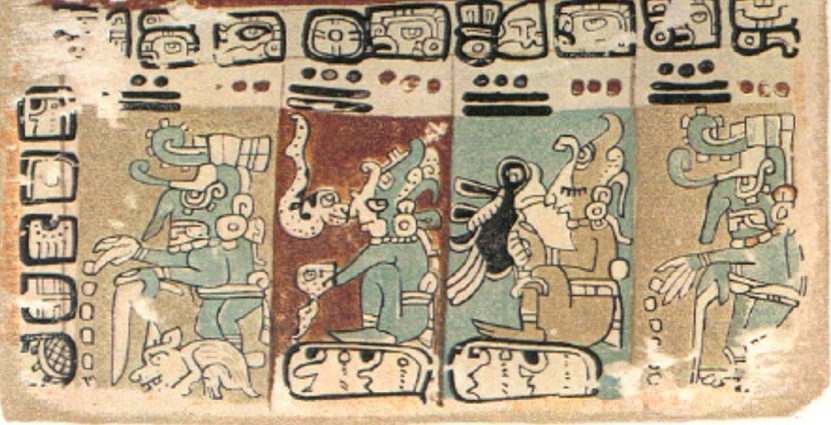

PRIMARY SOURCE I–Glyphs

Introduction The Mayans wrote thousands of books prior to the European conquest. With accordian-style pages made out of bark paper, only three of these books survive. One is called the Madrid Codex. Most of the content of the Madrid Codex is about agricultural ceremonies.

PRIMARY SOURCE II–First Person History

Introduction Diego de Landa was a Spanish bishop who traveled to the Yucatan to convert the Mayans. He was the person responsible for the destruction of most Mayan books. At the same time he wrote his own book, Relación de las cosas de Yucatán, which recorded his observations of Mayan culture and life. Ironically, it is because de Landa also recorded small parts of the Mayan language and hieroglyphs that centuries later archeologists were able to decode Mayan writing. The original manuscript of Relación de las cosas de Yucatán was lost, but copies still exist.

The commonest occupation was agriculture, the raising of maize and the other seeds; these they kept in well-constructed places and in granaries for sale in due time. Their mules and oxen were the people themselves. The Indians have the excellent custom of helping each other in all their work.

At the time of planting, those who have no people of their own to do it join together in bands of twenty, or more or less, and all labor together to complete the labor of each, all duly measured, and do not stop until all is finished. The lands today are in common, and whoever occupies a place first, holds it; they sow in different places, so that if the crop is short in one, another will make it up. When they work the land they do no more than gather the brush and burn it before sowing. From the middle of January to April they care for the land and then plant when the rains come. Then carrying a small sack on the shoulders they make a hole in the ground.

From Yucatan Before and After the Conquest, c. 1566, by Friar Diego de Landa, translated by William Gates, New York: Dover Publications, (1978), pp.37-38.

SECONDARY SOURCE

Introduction In recent years archeologists have discovered new Mayan sites which have revealed more about Mayan agriculture.

The ancient Maya civilization is widely recognized for its awe-inspiring pyramids, sophisticated mathematics and advanced written language. But research is revealing that the complexity of Maya agricultural systems is likely to have rivaled that of their architecture and intellect.

…

Fossilized plant remains . . . show that the Maya were growing crops such as avocados, grass species and maize. [Research] suggests that the Maya built canals between wetlands to divert water and create new farmland

…

As the Maya mucked out [dug out] the ditches, they would have tossed the soil onto the adjacent land, creating elevated fields which would kept the root systems of their crops above the waterlogged soil, while allowing access to the irrigation water.

“Mayans converted wetlands to farmland” by Amanda Mascarelli, Nature Magazine, November 5, 2010